Recently, in discussing utilization accounting and throughput accounting with colleagues, I recalled an intriguing thought from the software manager’s “Peopleware.” The connection between an exploitation mindset and utilization accounting is outlined in the following excerpt and article. I believe managers of creative services are required to work against utilization accounting and move their organizations toward a human-centered approach to management and motivation focused on continuous improvement for the better or kaizen.

Below is an excerpt from “Peopleware”. (Full book text.)

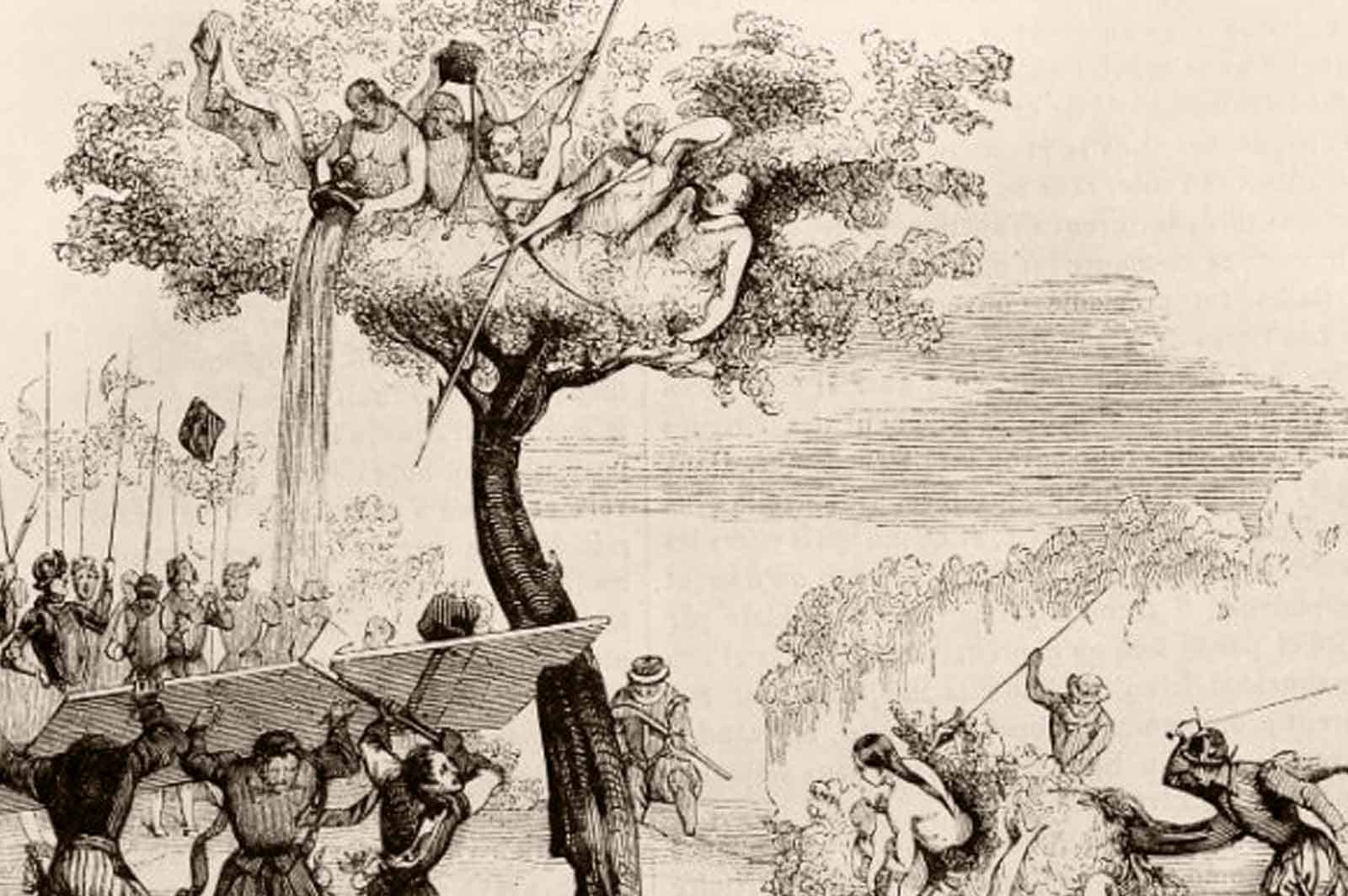

“Historians long ago formed an abstraction about different theories of value: The Spanish Theory, for one, held that only a fixed amount of value existed on earth, and therefore the path to the accumulation of wealth was to learn to extract it more efficiently from the soil or people’s backs.

Then there was the English Theory that held that value could be created through ingenuity and technology. So the English had an Industrial Revolution, while the Spanish spun their wheels trying to exploit the land and the Indians in the New World. They moved huge quantities of gold across the ocean, and all they got for their effort was enormous inflation (too much gold money chasing too few usable goods).

The Spanish Theory of Value is alive and well among managers everywhere. You see that whenever they talk about productivity. Productivity ought to mean achieving more in an hour of work, but all too often, it has come to mean extracting more for an hour of pay. There is a large difference. The Spanish Theory managers dream of attaining new productivity levels through the simple mechanism of unpaid overtime. They divide whatever work is done in a week by forty hours, not by the eighty or ninety hours that the worker put in.

That’s not exactly productivity — it’s more like a fraud — but it’s state of the art for many American managers. They bully and cajole their people into long hours. They impress upon them how important the delivery date is (even though it may be arbitrary, the world isn’t going to stop just because a project completes a month late). They trick them into accepting hopelessly tight schedules, shame them into sacrificing all to meet the deadline, and do anything to get them to work longer and harder.

Overtime for salaried workers is a figment of the naive manager’s imagination. Oh, there might be some benefit in a few extra hours worked on Saturday to meet a Monday deadline, but that’s almost always followed by an equal period of compensatory “undertime” while the workers catch up with their lives. Throughout the effort, there will be more or less an hour of undertime for every hour of overtime. The trade-off might work to your advantage for the short term, but for the long term it will cancel out.

Just as the unpaid overtime was largely invisible to the Spanish Theory manager (who always counts the week as forty hours regardless of how much time the people put in), so too is the undertime invisible. You never see it on anybody’s timesheet. It’s time spent on the phone or in bull sessions or just resting. Nobody can work much more than forty hours, at least not continually and with the level of intensity required for creative work. Overtime is like sprinting: It makes some sense for the last hundred yards of the marathon for those with any energy left, but if you start sprinting in the first mile, you’re just wasting time. Trying to get people to sprint too much can only result in a loss of respect for the manager. The best workers have been through it all before; they know enough to keep silent and roll their eyes while the manager raves on that the job has got to get done by April. Then they take their compensatory undertime when they can and end up putting in forty hours of real work each week. The best workers react that way; the others are workaholics.

People under time pressure don’t work better; they just work faster.

To work faster, they may have to sacrifice the quality of the product and their job satisfaction.”

——

The following article covers these concepts simply and thoroughly from an operations manager’s perspective: cost/utilization accounting vs. throughput accounting.

In helping organizations achieve their goals for process improvement, I have found the single most prevalent conceptual barrier to be the notion of throughput as opposed to resource utilization. Many, and possibly most organizations hinder their own process improvement efforts when they try to maximize individual resource utilization rather than trying to maximize throughput. Once they are able to move beyond utilization thinking, many other challenges fall away naturally.

The author cites Eliyahu M. Goldratt‘s “The Goal” in her thinking on the subject. The connections here are intriguing. The culture of the industrial revolution still pervades American management. As the author reminds us “… Turn of the 20th-century human beings was considered to be equivalent to machines, or perhaps more accurately, interchangeable machine parts, with the factory itself as the machine. Building on this assumption, the notion of human beings as “resources” became entrenched in mainstream management thinking very early on in the Industrial Age, and was taken for granted by the beginning of the Information Age.”

For managers to breakthrough conceptual barriers, new concepts of time must be developed. New metrics are needed. “Metrics that track the outcomes achieved rather than how busy individual resources are; metrics like throughput, cycle time, lead time, and process cycle efficiency. They begin to take advantage of the rarely-tapped creativity of their co-workers and the power of genuine teamwork, rather than locking people into narrowly-defined functional silos and trying to march them in lock-step along a static path.”

—

I am interested in your thoughts on these articles as they are certainly opinionated.

-Joe

2 Comments